You Have More Than 5 Senses. Here’s What It Means for Design.

We have more than five senses. Empathetic design in healthcare requires expanding our notion of how we respond to the built environment. From proprioception, which tells us where our body parts are relative to other parts, and equilibrium, which allows for us to “feel” gravity, our sense of hot and cold, hunger, thirst, and even time, how we engage with our surroundings is the product of a multisensory response.

Recent Corgan research and design solutions explore the possibilities of a more human, kinder, and effective design by understanding the several ways we experience our surroundings, uncovering the source common friction points, and testing intuitive technologies and interventions.

Sense of Time

No one likes waiting — especially in hospitals. According to NIH wait times are associated with overall satisfaction and can affect perception of information and care. Positive distractions from views of the outdoors, access to wander, and music can facilitate the perception of speedier wait times as can offering amenities for visitors and accompanying family.

Recently, healthcare design has invited furniture packages inspired by hotel lobbies — Methodist Midlothian Hospital, for example, offering guests high tops with plug and play capabilities to stay connected for work and entertainment. Elsewhere, patients and accompanying visitors are invited to wander—walk to the chapel from the main lobby and perhaps stop at the meditation garden.

Cut the Wait and the Waiting Room

At Village Health Partners in Frisco, Corgan eliminated the waiting room altogether—streamlining throughput and integrating technology to implement a self-rooming system that gives clients control of circulation from home to the exam room table. Finding new efficiencies in operations and limiting decision points, clients reduced wait times while physicians can spend more time with patients.

Learn more about self-rooming and how it reimagines a more effective delivery of care.

Proprioception

Balance issues. Uncoordinated movements or clumsiness. Poor posture control. While many of us take our ability to move for granted, the ability to sense our location, movement, and certain actions can be challenging for some populations including the elderly, those with brain injuries, arthritis, Autism, joint injuries, Parkinson’s disease and other common injuries and conditions.

Interference in the continuous loop of feedback that connects us to our body and shapes our sense of force, the weight of our actions, and variances in perception of anatomy can make simple actions especially difficult. For some, it may result in avoiding some activities such as walking on uneven surfaces or down long hallways.

Testing the suit in healthcare facilities, including Parkland Hospital, not only validated design strategies but also reframed how those with limited neck mobility and poor posture framed their spaces—calling attention to wayfinding opportunities on the floor as well as offering additional respite areas along circulation pathways.

Corgan Research: The Age Suit

Universal design emphasizes the democratized accessibility and experience of a healthcare facility’s diverse population—highlighting accommodations that advocate for the needs of the elderly, impaired, and special needs patients. As we continue to challenge design toward more empathetic solutions, Corgan’s experiments with a GERT—or aging—suit provide data and first-hand experience on how those with reduced mobility or challenges with proprioception may respond to the built environment. Adding 30 pounds and four decades, the suit mimics the experience of hand tremors, an unsteady gait, blurred vision, and joint stiffness.

Sense of Direction

A mix of cognitive mapping, special awareness, and cognition, our sense of direction speaks to our natural ability to orient ourselves through an environment. Determined by a mix of wayfinding mechanisms—signage, route monitoring, or our relation to nearby objects—our sense of understanding of location can also be impacted or limited by differences in language, ability, injuries, aging, or brain damage.

Retina Scanning Goggles

Capitalizing on innate decision-making heuristics, intuitive wayfinding responds to how humans subconsciously perceive their surroundings.

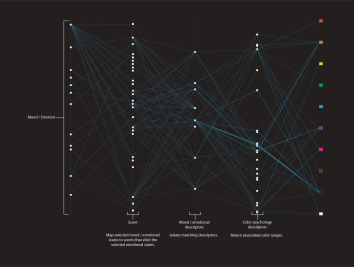

Using analytics from retina tracking, Corgan research applies data from user visual fields and fixation points to architectural gestures, lighting, memorable moments, and the location, color, and sizing of signage to reduce the complexity of the environment and facilitate a more intuitive patient journey.

Elsewhere, alternative directional markers add redundancies to account for the limitations of certain users. A leaf pattern along the floor at Parkland Hospital complements the prominent color-coding system to support those with color blindness.

Wayfinding packages tap into the power of layered applications that not only respond to our intuitions but also the various needs of a diverse group of users. Methodist Midlothian, for example, uses a mix of visual cues to draw users to key destinations. A large light installation brands the space and serves as the “front door” to the facility. Form and color complement subconscious decision-making processes to move patients and visitors through the space. Abstract ceiling forms, for example guide the eye and patient journey while light installations call out key destinations.

Fresh attention to how we feel our way through spaces and new research on how our traditional senses, including our sense of smell, shape our perception of the built environment uncovers new opportunities to innovate with intention and create a more empathetic future for healthcare design.