Designing the Workplace for Social Safety and Well-being

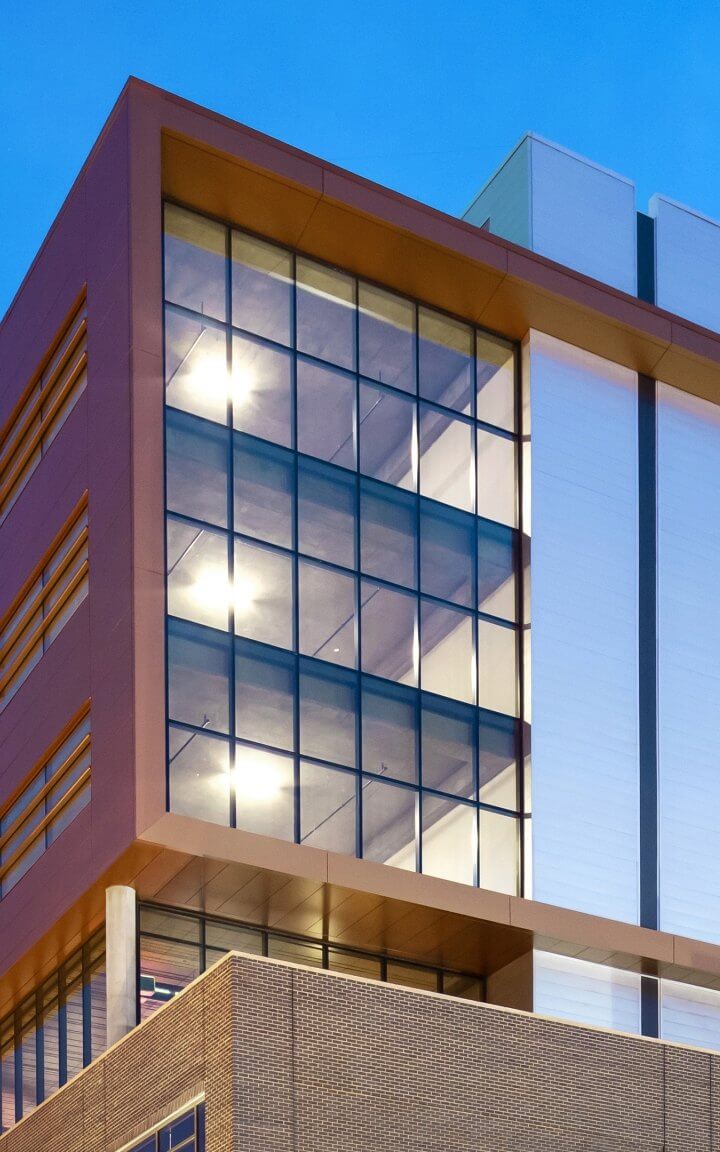

Glass walls continue a sense of open transparency throughout the Mannington Showroom in Atlanta.

Designing the workplace for social safety and well-being

Have you ever wondered why people choose to sit in certain places, rather than others? For example, why do people generally prefer restaurant booths over tables? Or at the office, why do people gravitate to conference room chairs that face the door?

Well, according to the Prospect-Refuge theory, first proposed by Jay Appleton in 1975, it is because people have an innate desire to seek out environments that feel safe. The theory posits that humans evolved to feel vulnerable in spaces where predators can approach without being seen. This means the ideal environment is one where a person can survey their surroundings while being protected from above and behind (refuge).

In hunter-gatherer times, this might have meant an overlook or a cave, but today we spend most of our time indoors. Yet we still seek out conditions that make us feel safe, particularly when facing the threats of the modern world. This is remarkably apparent in today’s office environment, where workers face a barrage of stressors and uncomfortable interactions. So how can we design the work environment to make people feel safe and comfortable?

Sadly, many workers feel threatened by their bosses or colleagues.

According to a recent survey, nearly one in five Americans are exposed to a hostile or threatening social environment at work. This can include verbal abuse or threats, humiliating behavior, unwanted sexual attention, bullying, or physical violence. (2015 RAND American Working Conditions Survey)

Under these conditions, visibility is key. Threatened individuals feel safer when there is less opportunity for concealment. This means avoiding situations where bullies may approach unseen or exhibit bad behavior behind closed doors. It is also important to eliminate spaces where workers may feel trapped, such as dead-end corridors. (Boomsma & Steg, 2011)

Simple design interventions may include glass office fronts and conference rooms, which provide visibility, even in closed-door meetings. Good light levels can improve feelings of security as well, particularly in confined spaces. For example, a brightly-lit monumental stair will feel much safer than a dark enclosed stairwell. Corgan’s design for the Playful headquarters in Mckinney, Texas is an excellent example of this with its central location and open metal structure, creating a strong link between all the floors.

When it comes to high-level planning, open office environments can address many of these safety concerns at once. Yet they need to be balanced with adequate opportunities for refuge. If not, threatened workers may feel they have nowhere to escape to. This leads us to our next challenge.

Open office environments can leave workers feeling vulnerable and exposed.

A recent article in Fast Company highlights the experiences of open office workers, specifically women, who feel uncomfortable being put on display. Many describe the sense of being observed constantly and scrutinized for their appearance. Furthermore, both men and women regularly complain about the lack of privacy in these environments. Where can one go to make a private phone call or to retreat from an uncomfortable situation?

This is where refuge spaces come in. By creating places where individuals feel protected from unwanted intruders, we can combat feelings of exposure and vulnerability. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways, ranging from dedicated privacy and wellness rooms to simple furniture solutions.

Many furniture lines now recognize this, responding with a range of high-back chairs and booth seating options. These designs align perfectly with Prospect-Refuge theory by creating environments where one’s back is protected. This effect can be enhanced further by adding protection overhead. For example, a dropped ceiling condition or large pendant light provides a sense of enclosure from above. (Terrapin Bright Green, 2014)

We can also design workplaces to avoid the uncomfortable sensation of having your back exposed to a door or aisle. While it's standard practice to lay out private offices with the desk facing the door, workstations often leave employees’ backs unprotected. By considering this during early space planning, we can increase workers’ feelings of security and privacy.

While it is important to create spaces for privacy and retreat, this must also be balanced with the desire for social connection and inclusion within the workplace. This brings us to our next challenge.

Social isolation can take an emotional toll on workers.

As the workplace relies more heavily on digital communication, it’s easy to understand how workers might feel socially isolated, and trapped in a barrage of emails, text messages, and web meetings. In fact, EY's recent study of belonging in the workplace showed that more than 40 percent of respondents felt physically alone or ignored at work. And this type of social pain can actually hurt. New findings from the field of social cognitive neuroscience demonstrate that social pain utilizes the same brain circuitry as physical pain. (Lieberman & Eisenberger, 2008)

Yet according to the EY study, one way of combatting this is through meaningful conversations with coworkers. Thirty-nine percent of survey respondents felt the greatest sense of belonging when colleagues checked in to see how they were doing both personally and professionally. By designing spaces that support community gathering and social interaction, we can help to foster these types of interactions.

Just as the kitchen is the heart of the home, break areas or work cafes often serve as the social hub of the workplace. We can encourage workers to frequent these spaces by creating warm inviting environments with access to daylight and comfortable seating. These welcoming designs can help to address the problem of dining "al desko" and inspire staff to come together, forming new communities and friendships.

In addition to a centralized gathering place, it is important to provide a variety of smaller communal spaces as well. These can range from enclosed conference rooms to open lounge areas – anywhere that encourages face-to-face interaction. Research from Herman Miller’s 2017 white paper, Belonging at Work, suggests that by designing spaces that support a sense of community belonging, companies can improve employee engagement and productivity as well.

Taken together, these design solutions give workers a sense of choice and control over their environment. They can choose when to be open to others, when to retreat for privacy, and when to socialize with their colleagues. By designing spaces that address each of these separate needs, we can help to support social safety and wellbeing for all.